CHAPTER I

When I was 19 years old I lived in a little place called Port Richmond,

Virginia, (now West Point, Virginia). In November of 1942 a few friends and I

decided to volunteer to join the Navy. We went to Richmond, Virginia and spent

the night in a hotel. I think it was the Jefferson Hotel. The next day we walked

over to the recruiting office and some of us were accepted in the service and

some of us were not. I was accepted in the Navy and I signed up for the duration

of the War. I went on a train to Great Lakes, Illinois for Boot Camp. At Boot

Camp we had to run around the base every morning before breakfast and we cleaned

the barracks. We had wooden floors and we had to get the black marks off the

floors and we scrubbed the floors with steel wool and if we did not get the

floors clean by meal time we had to get up earlier the next day to get them

clean. We slept in hammocks. The hammock was made out of canvas with ropes. It

was hung on about 4 inch pipes about four feet off the floor, the hammock was

pulled tight so it would not sag. You had to put a mattress, pillow, sheets and

cover on the hammock. Then you had to open it up to get in it to sleep. It was

hard to sleep on. Most of us fell in the floor several times. You were not

allowed to sleep on the floor; you had to sleep on the hammock. We took

immunization shots. We took shots in both arms. My right arm got so sore I had

to lift it with my left arm to put it in my pea coat sleeve. We had to keep our

barracks clean, our uniform had to be correct and we had to salute the officers

and salute the flag. If we did anything wrong we were punished. Sometime for our

punishment we had to get our sea bag and walk up and down the side walks or

sometime we had to work in the mess hall. We had to stand watch. While we were

in boot camp, I remember going on liberty and taking the train into Chicago,

Illinois. After we finished boot camp, we came home on leave. We reported back

to boot camp and got our orders. Some went other places but I went to San Pedro,

California and stayed there until I got my orders to report to the U.S.S. SANTA

FE CL60. While I was at San Pedro, California, I went on liberty and went to

Long Beach, California. I saw William and Sonny Hooper in Long Beach. They were

both from West Point, Virginia and had joined the service, William was in the

Navy and Sonny was in the Army.

In the early part of 1943 we reported to the U.S.S. SANTA FE. The SANTA FE was

built as a fast moving cruiser; she had twelve 6-inch rifles, and anti-aircraft

protection with 8 barrels of 5-inch, 40 millimeter and 20 millimeter guns. She

was a fast moving task force unit. The U.S.S. SANTA FE had rare Spanish-American

coins placed beneath the main mast. Some of these coins were from Santa Fe, New

Mexico. Miss Caroline Chavez christened the SANTA FE with water from the Santa

Fe River, which had been blessed by the Archbishop.

When we got on the ship we did not have to sleep in hammocks anymore, we had

bunks to sleep on. These bunks were on the wall and at night you opened your

bunk and slept on it and in the morning you put the bunk back against the wall.

We had rules in the mess hall. You could put what you wanted on your plate, but

you had to eat everything that you put on your plate. The SANTA FE had no women

on board.

The U.S.S. SANTA FE sailed from Long Beach, California to Pearl Harbor. We

reached Pearl Harbor on March 23, 1943. When we sailed into the Port of Pearl

Harbor we could see some of the damage that had been done to the United States

ships on December 7, 1941. We went on leave and walked on the beach. Walked

through the town and we went to a ranch and we rode horses. We left Pearl Harbor

and we anchored in Kuluk Bay, Adak, Alaska. The next day we headed west and

began going through the never-tobe-forgotten Aleutian fog. The first war mission

of the SANTA FE was a shore bombardment of Attu on April 16, 1943. The following

day Tokyo Rose announced that a battle ship of the SANATA FE class shelled the

Island of Attu. In May and June we had to patrol around Attu. U.S. Troops landed

on Attu on May 11th and this cruiser force was necessary to intercept any Japanese attacks. During

July and August the patrol was shifted to Kiska to soften it up before the

invasion. We bombarded Kiska on July 6 and July 22. On August 15, 1943, the

SANTA FE was covering the troops wading ashore at Gertrude Cove, Kiska. With

some relief we learned that the Japanese had somehow completely left Kiska. From

Kiska we went to Adak. After returning to Adak, the SANTA FE was to report to

CinCPac at Pearl Harbor.

When we returned to Pearl Harbor, after being in the Aleutian Islands, we went

on liberty. We went to the Nimitz Recreation Center and drank beer. We went to

the hula shows and we bought grass skirts as souvenirs.

In September 1943 we were in Pearl Harbor. On September 17, after days of

intensive drills, the task force 15 which included the SANTA FE started toward

Tarawa, a little Island in the Gilberts near the Equator. Early the next morning

all hands were at General Quarters watching the red and green lights of the

planes of the first strike. The Air Strike lasted all morning long on September

18, 1943. The first carrier raid had been a success and we headed back to Pearl

Harbor to await orders.

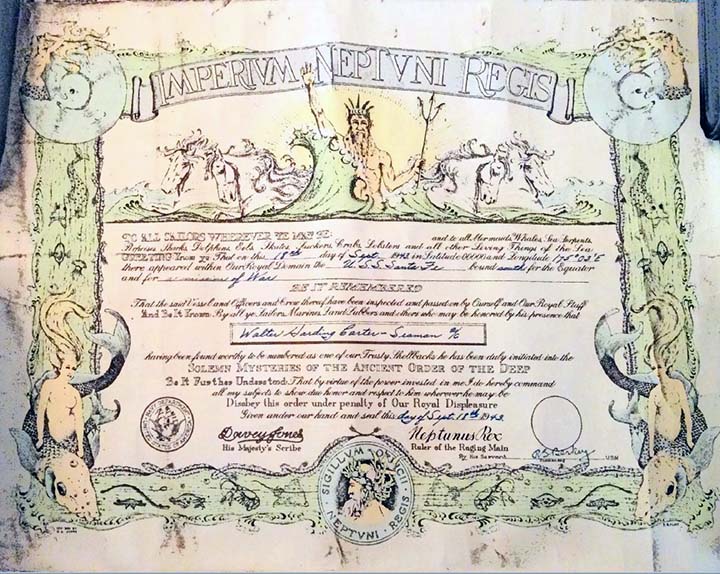

September 18, 1943 was the first time I had been across the Equator. With the

Captain’s announcement “Stand by for a bump when the Equator is reached”.

Shellbacks broke out razors and scissors, and immediately set to work carving

out the undeniable badge of the Pollywog, the partly shaved scalp. All of us had

to go through this initiation whether we were officers or not. We all had our

hair cut, some in baldy-cuts. This hazing went on all day long. We had to kneel

to King Neptune, bow at the Queen’s feet, drink from the Royal Baby’s bottle,

and kiss his belly. The Dentist gave us a mixture of soap, quinine and Diesel

oil as a mouth wash. We had to crawl through an airplane target, which was a

long canvas chute filled with garbage, oil and bilge water. While we were

crawling through this chute the Old Timers were on both sides hitting us with

paddles. After we had passed all of these tests, we were given a certificate of

King Neptune’s Domain. We were than called a shellback and we did not have to go

through this again.

We were at Pearl Harbor in October. From Pearl Harbor we went to Wake Island.

On October 5, 1943 we began shelling the enemy defense installations. After

about an hour this small Island was an inferno of raging explosions and fire.

The following day the planes bombed again. Then the SANTA FE headed back to

Honolulu.

The SANTA FE became a part of the Fifth Fleet on October 13, 1943 at Pearl

Harbor. The Fifth Fleet was on its way to the Central Pacific. The SANTA FE

headed north to Bougainville. The transport groups that were to send

reinforcements were there at sunset. At dawn on November 8, the Marines were

sent ashore. That evening a lone Japanese snooper saw the Marines and the ships

and gave the ship’s location to every Nip south of Tokyo. That evening about 30

to 35 twin engine “Bettys” made an attack with bombs and torpedoes. When a

torpedo is shot at your ship, you have to turn the ship to avoid being hit broad

side or you have to go straight into it so if your ship is hit, the torpedo will

bounce off your ship. Every ship in the group let loose with its anti-aircraft

guns until finally they lost so many planes they left. At this time I was in the

lower handling room sending up ammunition to the upper handling room so they

could send it up to the gun mount to be fired. Then about mid-night these planes

came back. Our ships guns sent them blazing into the sea one after another. One

flaming plane passed over the SANTA FE so close that its torpedo rack fell on

the main deck. .

After Bougainville the SANTA FE came back to the Gilberts for the invasion of

Tarawa to support the second Marines landing. Before dawn the SANTA FE was

bombarding the island as amphibious troops got into landing craft for the first

invasion of Japanese territory in the Central Pacific.

After two hours of steady shelling the Marines went ashore. Sniper and machine

gun fire killed a lot of the first wave. The SANTA FE closed to point blank

range for call fire. Many pill boxes made of concrete about seven feet thick and

these costal defense guns were shelled. The only way to get rid of these guns in

the pill boxes was for the Marines to go in with torches called flame throwers

and burn them. The Marines went in and destroyed the guns in the pill boxes.

This 72-hour battle for Tarawa cost over 3,000 in casualties. After the Marines

took over Tarawa there were very few palm trees left standing on the Island.

After Tarawa was in the hands of the United States, the SANTA FE went north to

make an air strike on Kwajalein on December 4th and 5th. After this air strike on Kwajalein in the Marshalls, we returned to Pearl

Harbor.

The SANTA FE arrived at Pearl Harbor on December 11, 1943. We stayed there for

two weeks. New Radar equipment was put on board. We were ordered to pick up the

Kwajalein Invasion Convoy and escort them out. On January 2, 1944 we were at

Terminal Island, U.S.A. The ship turned and went out to sea again for battle

practice maneuvers. We came in to Long Beach on January 3, 1944. Then we had

liberty; we had to sail on January 13, 1944.

On January 30, 1944 we bombarded the Island of Wotje. We left Wotje during the

night and went north to arrive At Kwajalein at dawn the next morning. The

bombardment started immediately we shot high explosive shells over and over

again. I was stationed on a five-inch gun mount. Later a spotting plane that had

been circling overhead dropped a cluster of flares, and the shells were lifted

to a point a few yards up from the water’s edge; then the troops landed behind

the curtain of fire and advanced up the island. Kwajalein was liquidated by

February 2, 1944. On February 16, after three days of cruising the force ran in

and launched six strikes unopposed on the Island of Truk. That night was etched

with tracer patterns as all ships beat off low-level torpedo attacks. The task

force’s total score for this one raid was 250 planes destroyed; 18 ships

including two cruisers, sunk. At dusk on the twenty first a “betty” was spotted

as it sneaked away. The Task Force moved toward Saipan and just after dark the

battle started. All night long the bogies went down in flames ignited by our

bullets. At sunrise the first strike was launched as the guns were still

blazing.

The SANTA FE got one ‘Betty” headed directly toward the ship. This plane

exploded so close to the SANTA FE that the flash would burn you.

On February 26 the ship anchored at Majuro. The following week the SANTA FE

went to Espiritu and joined Admiral Halsey’s Task Group. On March 20, 1944 the

force covered the invasion of Emirau Island.

On March 29, 1944, the SANTA FE was near Palau and Japanese torpedo planes

attacked from sunset until late that night.. No ships were damaged, but we did

destroy several enemy planes, after these strikes we went to Yap and were under

a heavy five-hour air attack Then we went to Majuro.

On April 13, l944, the SANTA FE left Majuro and went with Task Force 58 to New

Guinea for the invasion of Hollandia. On April 21 the carriers launched air

strikes to cover Hollandia. That afternoon a friendly plane was reported forced

down off Wakde Island. The SANTA FE sent two seaplanes to possibly rescue the

plane. The seaplanes landed near Wakde and rescued the pilot and crew of the

plane, which had been shot down that morning by Japanese anti-aircraft fire. The

SANTA FE only carried three seaplanes, which had to be launched off the ship.

These planes could land on the water and take off. These seaplanes had to be put

back on the ship with a crane and put in position so they could be launched

again.

The night of April 21-22 the SANTA FE and company were temporarily sent from

the carrier task group to support a bombardment of the air installations on

Wakde and Sawar. On the morning of the April 22, the SANTA FE and company opened

fire and sent over 10,000 rounds of five and six inch shells into the

installations on Wakde and Sawar on the mainland. The bombardment was done by

radar because the land could not be seen from the ship. The group then returned

to the carrier force. At dawn on April 22, 1944 MacArthur’s forces landed at

Hollandia and Aitape.

On April 26 the SANTA FE with the rest of the force left Hollandia and went to

Manus Island to refuel and to get supplies. The fuel was brought to the ship by

a tanker. We helped hook the hoses up and the tanker pumped it over to our ship.

The supplies were brought to our ship by barge and lifted on our ship with a

crane. We all helped with the supplies and put them in storage. We left Manus

and crossed the International Date Line on April 29. The next day, which was

another April 29, we launched an attack on Truk. On April 30 we also had

additional strikes against Truk and Satawan. On May 1, 1944 we struck Ponape

with air attacks and a bombardment.

We came to Port in Majuro. When the SANTA FE was in port we would paint and

repair the ship. Provisions came aboard at all hours. If we were looking at a

movie we had to stop and get the supplies aboard the ship. The crane on the ship

hoisted ammunition aboard from morning until night. We all removed it from the

cargo nets and carried it to the magazines. Each evening 300 men and 3 cans of

beer each, were taken to the Island for a few hours of relaxing. We could sit on

the beach, go swimming, and play ball or search for seashells.

On June 6, 1944, the SANTA FE left Majuro and was still assigned to the Task

Force 58.

Beginning June 11, 1944, we had daily air strikes against Saipan, Tinian and

Guam. We were shooting at planes on their runways and also to weaken the island

defenses. By June 16 we knew that a large Japanese surface force was

approaching. On June 19, 1944, our carrier planes began shooting their planes.

This was to be known as the First Battle of the Philipine Sea. From early that

morning the Japanese forces launched an all out air attack on our forces. By

evening our CAP had shot over 400 planes, this was the largest number of planes

shot for any one day of the war. This day was called “Marianas Turkey Shoot”. A

few of the Japanese dive-bombers did get through but they were shot down or they

dropped their bombs in the sea.

On June 20, our planes were sent to strike the Japanese fleet. Most of the

planes had to return to the ships at night and there was no moon shining. The

SANTA FE and all other ships turned on every light they had and fired star

shells, but still plane casualties were high. Destroyers went rapidly to places

where a plane’s running lights had disappeared into the sea and a great many of

the personnel were saved. This attack was a success for it had left the Imperial

fleet’s carriers crippled and no longer a threat to the Marianas’ Landings.

On July 4, 1944, the SANTA FE sometimes called the LUCKY LADY with Task Force

58 went to Iwo Jima for a bombardment. This bombardment demolished over 75% of

the buildings on Iwo Jima and hit most of the airplanes. During this time our

spotting plane was attacked by 3 Zeros. The radioman gunner shot down one of the

three before the SANTA FE’s riddled plane was forced to land. A rescue destroyer

picked up the crew from the water, and they were thankful to get back. The

radioman was shot in the leg.

On July 5, 1944, there was a Task force strike on Pagan. We had to get refueled

at sea. From July 6 to July 21, we launched daily air strikes on Guam and Rota.

After that we moved south for more air strikes against Yap, Woleai, Ulithi and

Palau. On July 28, the SANTA FE came with the carriers to the Marianas anchoring

off Saipan on August 2.

On August 4, the search planes saw a Japanese convoy leaving Chichi Jima.

Planes were immediately launched from the carriers to attack the enemy units.

After about five hours the DD’s in an attack group sighted and sank a small

oiler and a vessel similar to an LST. This group was ahead of the cruisers. At

about seven thirty a third ship was sighted and identified as a Japanese

destroyer. The SANTA FE and other cruisers opened fire immediately. The Japanese

destroyer returned accurate fire, but light. After about an hour the destroyer

sank. The survivors identified the ship as the destroyer MATSU . The cruisers

saw a cargo ship and they sank it. The units then searched north and east but

found no more of the convoy.

On August 5, 1944, the cruiser and destroyer group, including the SANTA FE

headed toward Chichi Jima. After several plane attacks were driven off with

anti-aircraft fire, the group formed into a bombardment position and bombarded

Fukamito Harbor. Enemy fire was accurate and one shot splashed close aboard the

SANTA FE’s starboard quarter, but the shore gun was destroyed before any damage

was done. The “cease fire” was ordered and we headed for port. The SANTA FE

arrived at Eniwetok.

While the SANTA FE was in Port at Eniwetok Island some of the men were given

liberty. To get to the Island the men got off the SANTA FE and got into a small

boat to take them to shore. When the men were in the small boat they thought the

Island was closer than it was and they were in a hurry to get to shore, so some

of the men jumped off the boat to swim to shore. There were about five men who

were not able to swim to shore. These men drowned and they were taken back to

the SANTA FE for a burial at sea.

On August 8, 1944 I was with a group of sailors in the bottom of the front of

the ship getting out paravane gear to put out for mines, the paravane gear would

destroy the mines before the mines could hit the ship. While we were getting out

the gear, the ship rolled and a steel table that had not been lashed down fell

over and hit me. The table weighed about three hundred pounds. I realized that

my foot was hit so I took off my shoe and I found out my toe was crushed into my

sock. I had no feeling in my left leg. Another sailor saw this happen and

immediately helped me hop to Sick Bay. My left great toe was badly crushed and

was bleeding freely from three lacerations, one along each side and a large

irregular one across the tip in such fashion that the end of the toe was

“duckbilled”. The nail was held on by a shred of tissue. There were visible bone

chips in the large wound and X-ray revealed a crushed facture of the proximal

phalanx. Other than the maceration of the wound edges, the wound was relatively

clean.

Treatment: Under local anesthesia, the wound edges were trimmed and cleaned and

all loose bone chips removed. Sulfanilamide crystals were freely dusted into the

wounds and they were closed with interrupted dermal suture. The toe was then

dressed and splinted. Healing was slow and complicated by a sloughing and

low-grade infection of the distal.

From August 8 until September 12, I stayed in bed most of the time and every

time I tried to get up and walk on crutches, my foot would swell up and I had to

get back in bed and elevate my foot. On September 12, 1944 I returned to duty

under treatment, because I still could not stand up for very long periods. My

foot never got well and I still feel the pain from the bony spurs in my foot

today.

The SANTA FE along with cruisers, Destroyers and the rest of the group made up

task force 38 and they left Eniwetok on August 30, 1944. We had gunnery

exercises and the Ancient Order of the Deep ceremonies and then the Third Fleet

launched strikes against the Palau Islands on September 6th and 7th. On the 9th an enemy convoy was sighted. This convoy was attacked by the carrier aircraft

on their first flight over Mindanao Island. The SANTA FE and group were detached

from the Third Fleet and sent to attack the remaining 22 ships, which attempted

to hide in Bislig Bay north of Sanco Point on Mindanao Island.

The SANTA FE fired over 1500 rounds of 6 inch, 5 inch and 40 millimeter guns

and sank four of the 15 ships she fired upon in this two-hour battle. The rest

of the ships were left burning. The Japanese craft did not damage the SANTA FE

group. Air strikes were continued against Mindanao Island on September 10th.

Air strikes were continued against the Visahyan area on the 12th through the 14th while we were near Dinagat Island. The same day more battleships joined the

Task Group.

An enemy bomber come over the ships and attempted a suicide mission to destroy

a ship, but he missed and landed in the sea.

During this time we had to fuel the ship, continue fighting, receive mail and

bury the dead. When we buried the dead we all came to the deck to show our

respect and we had a service for each sailor. We placed a flag over the body; we

had eight pallbearers to lift the body into the sea.

The SANTA FE’s two King fishers, which we call our seaplanes, went into enemy

held territory to the Camotes Islands where they rescued two aviators that had

been shot down, and these aviators were in the care of friendly Filipino

guerillas.

The Task Force Provided air support when the Marines went ashore on Pelelieu

Island then on the 21st the SANTA FE with the Task Force went toward Luzon to

provide air strikes against Manila.

After the first part of the Philippine fighting, the SANTA FE was anchored in

Kossol Passage, Palau Islands. This was close to the Japanese forces on

Babelthaup and the SANTA FE had to keep moving so the Japanese would not know

where we were. On the first of October 1944 the Task Group went to Ulithi, a

Caroline Atoll, and this became the base of future fleet operations,.

The sailors aboard the SANTA FE had many duties when we were at sea. We started

the day with reveille an hour before sunrise (about six O’clock). Almost any

time we would have – alert general quarters – which meant to get to our battle

stations. We had firing anti-aircraft sleeve practices, fueling the ship every

few days, receiving operation plans and receiving official U.S. Mail from a

destroyer.

The Gunner’s mates would guide the cargo net of ammunition to the proper place

on deck. We had to clean our guns after firing them. There were standing

condition III readiness watches, taking part in special training exercises,

launching and recovering “Gooney Birds” (these were the sea planes on deck). We

had the responsibility of rigging a towing spar for surface firing practice. We

had cleaning and maintenance work and training programs set by the Ship’s Plan

of The Day. These were some different duties we had to perform.

During October, we made air strikes against the Philippines and proved that the

carriers could successfully attack places protected by land based planes, and

could also defend itself against the planes. Landings were planned for Leyte in

late October.

The SANTA FE went from Ulithi October 6 with Task Group 38.3 and a few days

later made an all out air strike against Okinawa. From Okinawa we went to

Formosa and the Pescadores hitting them with heavy air strikes. That night on

the twelfth of October, the Japanese sent out their torpedo bombers. The Task

Force ships opened fire and the Japanese planes burst into flames. When the

battle was over that night the Task Force had suffered no damage.

On Friday the thirteenth the carrier planes were back over Formosa and the

Japanese waited until dark to attack. The Japanese hit the CANBERRY with a

torpedo in the bottom of her ship. She immediately asked for a tow and was

assisted. The group of the SANTA FE, BIRMINFHAM, MOBILE and six destroyers were

to escort and protect the CANBERRY which was being towed at about three knots.

All night the ships were busy trying to fight off the Japanese raids. The SANTA

FE kept the CANBERRY covered with stack smoke so the planes would not see her

and also managed to destroy one more Japanese plane. On the 14th the HOUSTON was hit by a torpedo and had to be towed. The BOSTON was towing

the HOUSTON and they were ordered to join the SANTA FE and her group.

At this time the Tokyo Radio broadcasts were boasting of how they had defeated

the U.S. Fleet and claimed the sinking of 20 carriers. Then the SANTA FE began

to send out plain language radio messages to give away the “Blue Fleet’s”

location, so the enemy planes would attack. Heavy enemy planes took the bait,

but just as they were about to come close, the enemy watch planes discovered the

Carrier Task Force and the Japanese Navy turned and ran from the very ships that

it boasted they had sunk.

On the sixteenth the SANTA FE took on part of the HOUSTON”S crew, these men had

been picked up from the water by another ship after the HOUSTON was torpedoed.

Throughout the day, our group was number one target for the Japanese air

strikes. No Japanese planes got through until evening when a Francis came

through the barrage and torpedoed the injured HOUSTON.

Just a few minutes later the SANTA FE was the target of a Japanese torpedo

bomber. All of the ship’s guns opened fire, the 5 inch, the 20 and 40 MM were

firing but still the Japanese bomber launched a torpedo at the SANTA FE, a

moment later the plane burst into flame and the pilot did a wing-over trying to

crash dive into the ship. All aboard including the survivors of the HOUSTON

braced themselves for an explosion. Under full rudder the ship turned sharply to

port, bringing the bow further from the fiery gasoline laden plane and swinging

the stern out of the path of the torpedo. The torpedo exploded harmlessly in the

water. During this time I was in the 5-inch gun mount with some other sailors

The Japanese plane was so close to the ship’s bow that the men operating the 20

MM guns were severely burned by the spattering, flaming gasoline. In this group

there were five Marines that got burned badly. These men were placed in the

Captain’s lounge on sheets, lying on the floor. They were burned so bad their

flesh was black. They were treated for these burns. I thought they would never

recover from these burns. Later when I saw them they had healed and I didn’t see

any marks on them. I was surprised that they looked so good.

I will tell you about the gun mount that I was in. We shot the 5-inch guns. The

ammunition was stored in the lower handling room and when it was needed it was

sent to the upper handling room. The guns were setting on the main deck and the

upper handling room was just below the guns. There was a spade-man to pull a

lever to put the spade down, a powder-man to put in the powder and then the

shell-man put in the shell and he pulled a lever and then the gun was ready to

fire. Sometimes the guns were set on automatic and some time they were fired

manually. If we were shooting at airplanes the guns were elevated high and when

the guns were fired sometime the powder can would come back into the gun mount

and the sailor with asbestos gloves on would grab the hot powder can and throw

it out of the chute.

The SANTA FE turned her attention to the HOUSTON, which had been hit two times.

When the smoke cleared away you could see how much damage had been made to her

main deck. She had an added list in front, but the men doing repairs kept her

going and we did not have to reduce the slow towing speed. There were attempts

that afternoon to finish sinking the HOUSTON and the CANBERRA. The CABOT and the

COWPENS kept the planes from getting through.

October 17, 1944 was spent taking portable pumps to the HOUSTON, water to the

CANBERRA and fuel to two Destroyers. Japanese planes were spotted that evening,

but friendly planes kept the Japanese from reaching the Task Group. Late that

afternoon the HOUSTON survivors were transferred from the SANTA FE to a Tanker.

After the survivors were transferred the SANTA FE was ordered to return to her

original Task Group 38.3

These days of protecting the crippled ships had been hard for the SANTA FE. We

had to spend long hours in cramped general Quarters Stations waiting for and

fighting off enemy bombers and we had to watch out for submarine attacks on the

slow, crippled force. We had extra fueling to do and we had to care for 200

extra men. That was all over and now we were headed northwest to join the Task

Force 38.3 and prepare to invade the Philippines.

WALTER HARDING CARTER

SAILOR 1945

U.S.S. SANTA FE 1945

CHAPTER 2

October 23, 1944 was the beginning of the second battle of the Philippines. The

SANTA FE was in a Task Force within the Third Fleet. An enemy surface force was

sighted. We knew they were going to strike and at about mid night the first

planes began closing in and all hands to their battle stations was called. The

planes stayed all night, but they stayed out of firing range most of the time at

about 20 to 25 miles away.

The next morning search patrols were launched and they saw about 40 planes and

as the planes were taking off from our ships, another 30 enemy aircraft were

spotted. With so many airplanes in the air the radar screen could not be

depended upon and visual sighting had to be used. The anti-aircraft guns, the

five-inch, 40 and 20 MM, were being fired continuously. It was hard to tell

friends from the enemy. The men in the lower handling room felt a bit of relief

when it was discovered these planes were dive-bombers and not torpedo bombers.

One of the dive-bombers dove at the HEALY and just missed it. Another

dive-bomber hit the PRINCETON on her hangar deck and she had to drop from the

formation. THE BIRMINGHAM tried to rescue the PRINCETON by pouring streams of

water into her. Suddenly the PRINCETON blew up violently causing both boats to

have hundreds of casualties. While this battle kept going on, the ESSEX and the

LEXINGTON sent out search planes and discovered the Japanese planes were carrier

based planes and they were approaching from the North.

About noon while we were busy with launching and recovering operations, another

group of Japanese planes began to attack. The sky was full of planes. We

launched more planes and two raids were broken up, but one group of enemy planes

got through and into the formation. Three dive-bombers got through and a torpedo

bomber made a run; The SANTA FE port and starboard batteries opened fire. The

ships in the formation turned, zig-zagged, evaded, and luckily no hits were

scored.

Our search planes made contact and reported a Japanese Carrier force of about

26 ships about 190 miles northeast. Halsey made a decision to leave San

Bernardino unguarded so that we could attack this new group. His plan called for

early morning air strikes from all of the Task force 38, he wanted the surface

vessels to go ahead of the carriers and finish off anything that was left. The

plan seemed perfect. The Japanese were only 44 miles away; the first strike had

good hits over target. Just as we were going to finish off this group, a third

Japanese fleet was sighted back in San Bernardino Straits. As soon as this was

known, the main striking forced of the Third Fleet made a 180 degree turn to

return to San Bernardino and counter this new Japanese fleet.

The SANTA FE was given tactical command of a cruiser destroyer group, that

group was the MOBILE, WITCHITA, NEW ORLEANS and 12 destroyers. This group was

ordered to go North and catch and sink any damaged ships. Two carriers had

aircraft that stayed and continued to fight the enemy. A surface craft was

picked up by radar and soon a Japanese carrier could be seen. No planes could be

seen on the Japanese carrier but the crew was still on board. As soon as the

Japanese carrier came in range all four cruisers opened fire. With steady fire

from the guns from the four cruisers, the Japanese carrier later identified as

the CHITOSE capsized and went under.

As soon as the Japanese carrier had gone down, the cruisers continued on. A

LANGLEY plane sighted the Main enemy group consisting of many ships about 40 to

50 miles away. Later there was reported surface contact at about 17 miles, some

of the same ships. Now that it was dark, the men on the main deck could see

nothing. but the radar scope showed three pips and the distance between them was

rapidly closing. THE SANTA FE and MOBILE were directed to fire at the closest

targets, and the heavy cruisers were to fire at the distant targets. At about

7:00 O’clock the main battery opened fire and shortly thereafter the secondary

battery also began firing. The night was aglow with red tracers going toward the

target. The Japanese ships returned fire through out this battle. There were

some “short” and some “over” fire seen but did not hit the target. With some

fires breaking out on the Japanese ship, the ship was still able to make speeds

up to 28 knots. At about 9:30 O’clock the 5-inch mounts commenced shooting star

shells and lighting up the sky and the SANTA FE came into almost point-blank

range and continued firing. The range was about 4800 yards now, and the majority

of the shells hit and the Japanese ship sank. This ship was later identified as

the OYODO or AGANO class.

At about 10:00 O’clock it was reported the nearest target was 43 miles north.

Since fuel was needed before much longer, the force was to join the carrier

groups. The next day the SANTA FE was refueled and joined Task Group 38.3. She

went to Leyte Gulf in a covering position, until she was ordered to proceed to

Ulithi. That was the SANTA FE’s part in one phase of the greatest battle of all

time. The Japanese had suffered many losses and would never again be able to

control the Pacific Waters.

The SANTA FE was in port about two days and then we headed for Manus. Later

that evening on November 1, 1944, the fleet course was changed to go to Leyte to

counter a Japanese naval thrust. On November 3, while we were traveling through

heavily mined waters, the Task Group was attacked by a Japanese Submarine, which

shot a torpedo into the RENO forcing her to retire to port. Air strikes against

Luzon were ordered. Japanese air power, although reduced was still able to

attack against the landing forces at Leyte. On November 5, the Task Group’s

planes hit Manila and at the same time the Japanese sent out suicide planes,

which attacked the formation just after the noon meal. One plane crashed on the

LEXINGTON, one near the TICONDEROGA and a third pane was shot down.

On November 11, 1944 the Task Force destroyed an entire convoy of Japanese

reinforcements for Leyte that were in the Camotes Sea.

The next day was refueling day and on the 13th and 14th the Task Force made strikes against the manila area.

The SANTA FE returned to Ulithi. During our stay at Ulithi I was driving

whaleboat number 2 from the SANTA FE to the dock for the sailors to go on

Liberty and then I would pick them up from the dock and bring them back to the

SANTA FE. Sometime when I was driving the whaleboat the waters would get rough

and the ocean spray would come over the boat and hit me in the face this ocean

spray contained salt and it would make my eyes hurt. When whaleboat number 2 was

needed, the Coxswain would blow his whistle and get on the loudspeaker and say

whaleboat number 2 launch your boat. The crew would get in the boat and go to

the gang plank and the officer of the day would give me my orders of what to do

and where to go. On this whaleboat I was in charge, I had a bell to ring to give

the engineer his orders. I took my orders from the Officer that was on duty. On

whaleboat number 2 I had an engineer and a bow hook man. The engineer was

supposed to run the motor and the bow hook man was supposed to catch the

gangplank of the ships and hold the boat beside the gangplank for passengers to

get on and off. When we went back to the SANTA FE he was supposed to catch the

boat boom and tie the boat up until we got the orders to go again. One time I

was sent with my orders to carry movies to other ships and trade them for

different movies, I also had a sailor on board that needed to be put on a larger

boat. I took the movies to the other ships and carried out all my other orders

and it was so rough when I tried to put the sailor on the larger boat I had a

hard time doing it. I went along the side of the large boat for him to get off,

the waves were so rough that it was hard for him to get off and in order for him

to get off, the large boat had to get underway and then I would try to get along

beside the large boat for him to jump on the large boat but that didn’t work

because the large boat rolled my way and caught the side of my boat and tore my

boat. At that time the passenger sailor jumped off and the bow hook man jumped

off with him on the larger boat. I could not get back close enough to the large

boat to get the bow hook man back. The waves kept rolling and whaleboat number 2

and the other large boat kept hitting together. So I went back to the SANTA FE

and it was so rough that every time I would rise up to the boat boom on the

SANTA FE, the whaleboat would fall with the swells of the ocean and after trying

for a long time, I finally got whaleboat number 2 tied up to the boat boom. Then

the crane from the SANTA FE lifted the whaleboat out of the water and put

whaleboat number 2 in the hole of the SANTA FE. I did not see the bow hook man

for a few days. I worked on the whaleboat with other sailors until the damage

was repaired on whaleboat number 2.

On November 20, Japanese midget submarines came into the harbor to torpedo and

sink the fleet tanker MISSISSINEWA. A SANTA FE aviator and his radioman became

heroes by taking a sea plane and rescuing the survivors.

On November 22, 1944 after the SANTA FE had been refueled and received supplies,

we headed toward the Philippines with Task Force 38.3. On November 25, while

firing at northern Luzon, heavy Japanese air fire was met and the ESSEX was hit

with a Japanese dive-bomber on her flight deck. Within minutes the fire is

controlled and the ESSEX is able to stay in formation in the Task group. The

SANTA FE shot down another dive-bomber as it began its dive. These strikes were

continued until December 2, and then the Task Group went towards Ulithi,

On December 10, 1944, the SANTA FE with the Task Force headed for Luzon, to

keep the Japanese air force from attacking the troops of South West Pacific

while they were going ashore and getting established there.

During December 14th 15th and 16th the Third Fleet ‘s planes were hitting the airfields of Luzon both day and

night. Only a few Japanese planes came near the SANTA FE’s formation and none of

the planes attacked the ships.

On December 17, a heavy typhoon was forming to the east and was headed directly

for the Task Force. The typhoon caught the Task Force Group directly in its

path. After winds read 80 – 90 knots, the ship takes a 52-degree roll to

starboard. The SANTA FE rides out the storm without major damage. There was

minor breakage. Eight ships in the Group were damaged and some were sunk. Some

had to return to Ulithi and repair the storm damage. The Task Group took a final

look for survivors before they returned to Ulithi on Christmas Eve.

On December 24, the SANTA FE returned to Ulithi to learn that we were not going

back to the states for our yearly overhaul. The day after Christmas we saw our

sister ship MOBILE pull out and head for the States to take her yearly overhaul.

But the SANTA FE stayed and broke the record of being longer without an overhaul

than any other ship. On December 25, we took on more supplies of ammunition and

food.

I was on the SANTA FE and in the Third Division. The Third Division loaded

5-inch ammunition and manned gun mounts 51,52, and 53. We were at the loading

machines and in the gunrooms. Everyone had to help with refueling and taking on

supplies. We also had to practice loading the guns and handling the powder and

the shells. One day while we were firing the guns, the spade man had not put the

spade down and the man with the powder put the powder in before the spade, when

the man with the shell saw that the spade was not down and the powder was going

out of the chute, he jumped out of the gun mount to the deck below, with the

shell in his hands, because he thought the powder can would blow up. The powder

did not explode; it just got bent and went out of the chute to the deck where

all of the empty cans go after they are fired. When I was in Port, I drove

whaleboat number 2 to take movies from one ship to another, take sailors on

liberty, take officers from place to place and I went wherever I was ordered to

go.

The SANTA FE could carry no more than three “King fisher” seaplanes. The SANTA

FE could carry two seaplanes on deck and one in the hole. Sometimes we had two

planes or less. The water was so rough sometimes the seaplane would come in for

a landing and turn over and wreck. The anti-aircraft fire and Japanese Zero

fighters would keep the “Gooney Birds” from getting back to the ship.

On December 30, 1944 the SANTA FE and the rest of the Task Force 38 left Ulithi

with orders to go to the Lingayen area for air strikes against the Japanese

planes.

On January 3rd and 4th 1945 we launched air strikes against Formosa and on the 6th and 7th we launched air strikes against Luzon. On the 9th, which was McArthur’s Luzon Dog-Day, the Task Force 38 had planes attacking

Formosa’s airfields trying to keep the Japanese planes from hitting the men

landing at Luzon. That same night Halsey ordered the Task Force to go through

Bashi Channel into the South China Sea. On January 12 Camranh Bay and Saigon,

Indo-China were hit.

On January 17, 1945 when we were gong for a refueling, the SANTA FE passed her

200,000-mile mark. The siren and whistle were heard, celebrating this event. We

were all thinking, we will be going back to the States soon. One sailor started

the rumor that we were going back to the states and when the rumor (scuttlebutt)

got back to him, he believed it himself. When we were trying to refuel the SANTA

FE and the tanker came beside us to give us fuel, the sea was so rough that it

was hard to get the hose to pump the fuel oil to the SANTA FE We pulled the hose

aboard our ship and hooked the hose up and were pumping the oil and the waves

were rolling and the ships were rocking back and forth and the hose broke apart.

The tanker was still pumping the oil, and before we could get the tanker to stop

pumping oil to the ship, the oil went everywhere, onto the decks and covering us

with black oil, this oil was hard to get off. We had to clean up this mess.

We had air strikes against Takao on Formosa, Amoy and Swatow on the China Coast

The Task Force also hit Hong Kong and Hainan Islands.

Tokyo Rose had announced on the radio that an American Fleet could never enter

the China Sea. We got in and then she said the Fleet could never get out. Task

Force 38 got in the China Sea and got out. Tokyo Rose was educated in the United

States and she could speak English well. We could hear her on the radio on the

U.S.S. SANTA FE. Tokyo Rose wanted to upset all the Navy men so they would worry

about everything and they would not be able to do their jobs well. Tokyo Rose

said your girlfriend is at home in the United States and she is running around

with other men and you are over here fighting for your country. She said the

U.S.S. SANTA FE was sunk. Tokyo Rose also said that other ships were sunk. We

found out later that the other ships were still fighting.

On January 21st and 22nd we went back and hit Formosa and Okinawa with heavy air strikes again. We knew

we had done a good job over there and the Third Fleet went back to Ulithi.

We knew that we had to hit the Japanese Empire like they had hit the United

States when the Japanese planes hit Pearl Harbor.

On February 9, 1945, the Task Force 58 left Ulithi and headed straight for

Tokyo for a carrier bombing of the Japanese capital. We made successful air

strikes on Tokyo on February 15th and 16th.

The SANTA FE left the Tokyo area on the 18th to go as a fire support unit for the invasion of Bonins. This was the SANTA

FE’s 12th and last bombardment of the Japanese Islands. This was the third time that the

SANTA FE had covered the beachheads for the Marines to land.

You could see hundreds of ships in the early morning of February 12, 1945 when

the SANTA FE began shelling the southern beaches of Iwo Jima. The shelling

increased as many landing craft headed toward the Island. We were on the SANTA

FE and we were firing both 5-inch and 6-inch guns and then stood by right off

shore for call fire.

I was in the 5-inch mount and it was difficult to fire these guns because we

could not see the Japanese gun positions from out ship. The rear seat Marine

spotter that was in one of the search planes was fatally injured by flak. He was

pointing out new targets when he was hit.

For two nights the SANTA FE kept firing these guns and we were also firing star

shells over the island. Heavy fire was ordered in the morning as the Marines

advanced and secured their position. At about noon on the 21st after two and one half days of living at battle stations, the SANTA FE was

relieved by the NORTH CAROLINA. We had shot over 4000 of our shells into the

pillboxes and blockhouses of Iwo Jima. We were tired and glad to leave the

battle stations and we knew that we had done the best we could.

On February 16, 1945 the Fifth Fleet launched a heavy strike against Tokyo. I

was on the SANTA FE and we were surprised we did not have more resistance that

day.

The SANTA FE left the carrier force on February 18, but after a brief stop at

Iwo Jima we rejoined the carrier force for the second raid on Tokyo on February

25. It was apparent that the Japanese air force and fleet could not defend their

homeland. These last two raids had damaged and destroyed over 650 Japanese

planes and sank and damaged over 50 ships.

The last of February, with the success of these two raids, the U.S.S. SANTA FE

left the Japanese waters and headed for Ulithi

While we were at Ulithi, all of the ships were refueled and were fully loaded

with ammunition.

On March 19, 1945 when Task Force 58 was launching an air strike against

Shikoku and Kyushu, a Japanese bomber came out of the low clouds over the bow of

the FRANKLIN and went the length of her flight deck. This Japanese bomber

dropped two 500-pound bombs on the FRANKLIN. The first bomb hit near the bridge,

the second 500-pound bomb hit the flight deck and the parked airplanes. There

was a tremendous explosion. The FRANKLIN (Big Ben) was a 27,000-ton carrier.

Fire consumed the airplanes and shot up and swept the fantail and some of the

men jumped and some were knocked overboard.

There were almost 1000 men dead or missing and about 200 seriously wounded.

This was one of the largest single disasters in the history of the United States

naval warfare. No other United States ship has ever survived that much damage.

The fire was so hot that big girder twisted like taffy and the steel melted into

liquid. The ship had just taken on all the ammunition it could carry and some of

this ammunition burst into flame. Captain Gehres of the FRANKLIN was steaming

crosswind to control the smoke. Rescuers were risking destruction to help the

crippled carrier. Among them were the destroyers HUNT, MARSHALL, TINGLEY, HICKOX

and MILLER and the light cruiser SANTA FE

Captain H.C. Fritz of the SANTA FE came up on the starboard side of the

FRANKLIN and asked, “are your magazines flooded?” He was remembering the SANTA

FE’s sister ship the BIRMINGHAM last fall when she tried to help the PRINCETON

and the PRINCETON exploded and there were a lot of casualties on both ships. Now

there were at least 4,000 men’s lives at risk.

The next explosion was a five-inch service magazine. Some of the wounded men

were being transferred when the magazine exploded. Flame and smoke shot about

7,000 feet in the air. There were pieces of armor plate being tossed around. The

first wounded man was taken on the SANTA FE at about 10:00 O’clock that morning,

crossing the water on a stretcher on the lines. The SANTA FE could not keep her

position alongside the FRANKLIN because of the FRANKLIN’s drift. The SANTA FE

then cast off, circled and then made a magnificent approach and came back in at

25 knots at a wide angle. The SANTA FE slammed against the FRANKLIN and held her

with the SANTA FE’s engines. At this time the FRANKLIN was listing 14 degrees

and still blowing up. The FRANKLIN was a much larger ship than the SANTA FE and

when we slammed against her, part of her flight deck was over the SANTA FE.

The SANTA FE got five large hoses going and many of the crewmen began fighting

the fires. Leaking gasoline helped spread the fires. These were brave men that

kept the hoses going with shrapnel flying in the air.

Men began jumping from the FRANKLIN to the SANTA FE some were jumping in the

sea and some were dropping down lines to the deck. The men were getting on he

SANTA FE any way they could. Finally a catwalk was placed from the flight deck

of the FRANKLIN to the top of one of the SANTA FE’s gun mounts. Some of the men

that fell into the sea were never seen again. Rescue ships recovered over 1700

men from the FRANKLIN. The SANTA FE had almost half of these men.

The U.S.S. PITTSBURG also helped rescue the FRANKLIN.

Some of the sailors on the SANTA FE gave up their bunks and clothing to these

survivors. One sailor from the FRANKLIN told me he was looking for his brother

who he said was on the FRANKLIN with him. I don’t know if he found his brother

or not. I do not remember seeing that sailor again.

On March 24, 1945 the SANTA FE came to Ulithi.

On March 26, the SANTA FE left Ulithi with the damaged FRANKLIN.

On April 10, 1945 the SANTA FE came in to Terminal Island, U.S.A. When we came

in Dinah Shore was Singing. I remember her singing “Oh What a Beautiful Morning”

and she sang song after song. Dinah Shore came aboard the SANTA FE. She kissed

one of the sailor’s white hats. Dinah Shore gave autographs to some of the men.

There were men of faith on the SANTA FE. There were men of many denominations

and faiths on board. We had a chaplain who held services aboard the ship on

Sunday.

On May 29, 1945 when we were in the states my eyes were still hurting and they

were blood red, so I went to sick bay and they gave me my medical records from

the ship and I was sent to the U.S. Naval Hospital, Long Beach, California. At

the Hospital they examined my eyes and said it may have been a blood vessel that

ruptured in my eyes and they gave me drops for my eyes. My foot was also hurting

so they examined my foot too; they said I had tenderness on touching skin over

distal scar of left great toe. Probably there is a small neuroma, which could be

the cause of the pain. The Doctors at the U.S. Naval Hospital said I could be

sent in for study and possible surgical procedures or the scar and possible

neuroma could possibly be removed on the SANTA FE X-rays taken at the U.S. Naval

Hospital revealed a small fragment of osseous tissue which may be blocking the

distal joint.

By July 16, 1945 the SANTA FE was completely overhauled from keel to topmast.

The SANTA FE went to San Diego and the SANTA FE would soon be going to join the

fleet.

On July 26, 1945 the SANTA FE headed to Pearl Harbor and we were ready to spend

another two years at sea.

The SANTA FE was at Wake and then the SANTA FE spent three weeks at Okinawa’s

typhoon – plagued Buckner Bay

On September 25, 1945 the SANTA FE came to Sasebo and stayed there for a few

days. While we were at Sasebo a surrender delegation was ordered aboard the

SANTA FE. I was standing on the deck of the SANTA FE when the surrender

delegation came aboard. The sailors could go ashore on Sasebo. We saw the

Japanese people, geisha houses, department stores and trolley cars.

On October 8, 1945 the SANTA FE left Sasebo. A Typhoon came up and forced us to

stop at Nagasaki and this gave all of us time to look at all of the destruction

that the atomic bomb had made in Nagasaki. I drove whaleboat number 2 to

Nagasaki; we were taking the officers to see how much damage was done to

Nagasaki. There was nothing left of Nagasaki but ashes. I saw an old gas mask on

the shore. In the water I saw little wooden boats that had been filled with

explosives so the Japanese could commit suicide by hitting our ships with these

little boats and blowing up our ships.

The first port that we visited on Honshu was Wakayama.

The SANTA FE went to Yokosuka, located at Tokyo Bay’s entrance. While we were

there we could visit both Tokyo and Yokohama. While we were on liberty we

visited the Emperor’s Palace and the Imperial Hotel. We had some places we could

visit and some placed were off limits. When we were in port I would be driving

whaleboat number 2 and I was taking the sailors to shore when they had liberty.

One day I saw the old battleship NAGATO with her guns made useless and her

powder magazines empty, she was one of the reminders of the once proud powerful

Japanese fleet.

On October 17, 1945 Captain Fitz was transferred from our ship and Captain

Freeman became the Captain of the SANTA FE. Within hours of becoming captain of

the SANTA FE Captain Freeman was ordered to go to Ominato KO.

We went to Otaru Hokodate, and Aomori and came back to Ominato on November 4,

1945.

After the war was over there were some rifles that had been captured from the

Japanese army. These rifles were placed on the deck of the ship and we were told

we could get one of these rifles for a souvenir if we wanted one. Each sailor

that wanted a rifle had to get a permit to carry the rifle. I got a permit and

got one of the rifles. I had a hard time bringing the rifle home. I could not

mail the rifle home. The only way to get the rifle home was to carry it. I kept

the rifle in my possession until I got home. I still have that rifle today.

On November 14, the flag was transferred to the QUINCY and the U.S.S. SANTA FE

became part of the Magic Carpet operation.

On December 17, 1945, I was examined for discharge from the Navy and after my

examination, when the defects were noted; I was found to have Pterygium in both

eyes and Varicocele in my left foot. For the rest of my life I will have to live

with both my eyes hurting and my foot hurting too.

During this time that I was in the Navy on the U.S.S. SANTA FE we had liberty

some time. I remember going on liberty and spending a few hours on Mog-Mog’s

Coral Beach, I remember diving down in the water, swimming around, looking for

sea shells, relaxing, sitting on the beach, drinking beer, eating peanuts, and

talking about what we would do when we were on liberty in the States.

I was on the SANTA FE when we left Long Beach. California in 1943 and I stayed

on the SANTA FE until I was discharged from the Service in December 1945.

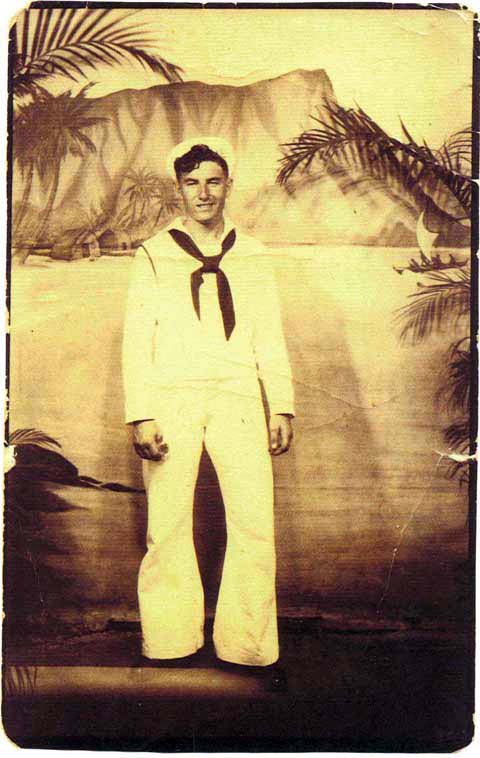

Hawaii 1945

Walter Harding Carter

Two Sailors

Edmond Borinski and Walter

Harding Carter

Carter Neptune

Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal 2

Silver and 2 Bronze stars

Back of Asiatic Pacific Campaign

Medal 2 silver and 2 bronze stars

Navy Occupation Service Medal

Asia

Back of Navy Occupation Service

Medal Asia

WWII Victory Medal

Back of WWII Victory Medal

.jpeg)

Honorable Discharge Button,

Combat Action ribbon, Honorable Service Lapel Pin (Ruptured Duck)