|

Support of the landings at Lingayen Gulf, the final operation of consequence in the Southwest Pacific, was the task group's next concern. Light cruiser SANTA FE left Ulithi with the carriers 30 December, proceeded northwest, and stood by 3-4 January 1945 while strikes were launched against Formosa and the southern Ryukyus. Adverse weather conditions prompted the carriers to move southward to Luzon, where strikes were delivered 6-7 January. All ships fueled on the 8th and returned to hit Formosa 9 January 1945. Passing through Bashi Channel the night of 9-10 January, the task force proceeded southwest through the South China Sea. On 12 January Navy carrier planes sank 127, 000 tons of merchant and minor naval shipping in the south Indo-China area. Through holes in a thick overcast, shipping at Takao, Amoy and Swatow was bombed on 15 January; Hong Kong and Hainan were tackled on the 16th. Fueling operations, which had been hampered by the continuing heavy weather, were finally effected on the 19th, when good weather was found in the lee of Luzon. On 20 January 1945 the task force steamed northward out of the South China Sea. Exit was made through Balintang Channel, and on 21 January the carriers launched strikes on Formosa from a position southeast of the island. Without warning or previous contact, two enemy planes dove on the formation at 1145. One of them took a dose of hot steel from the SANTA FE, dropped a small bomb on the carrier LANGLEY, and high-tailed it home; the other dashed himself against the TICONDEROGA. Other enemy feints were later made, none of which reached Task Group 38.3. Okinawa was hit 22 January, the final air strike of the 27-day operation. Having rolled up 200,000 engine miles since her commissioning, cruiser SANTA FE arrived with her task ,group in Ulithi Lagoon 26 January 1945. Upon arrival, the carriers and their escorts reverted to the Fifth Fleet. With the revamping of the task force, SANTA FE was assigned a unit of Task Group 58.4, and as such left Ulithi on 10 February 1945 for air strikes against the Japanese home islands. Going south of Guam, the SANTA FE bobbed up off the cost of Honshu 16 February and skirted the carriers of Task Group 58.4 as they dispatched their aircraft into misty, ashen skies. Destination: Tokyo, some 150 miles to the northwest. This first strike against Japan proper since Doolittle's "Shangri-La" token raid in April 1942 was a diversionary tactic in conjunction with the Iwo Jima landings to the south. On the evening of 18 February, the SANTA FE was detached for fire support work at Iwo. Early on 19 February the SANTA FE went to General Quarters for the pre-invasion bombardment of Iwo Jima. At 0645 her 6-inch guns began gouging huge chunks out of Iwo Jima from a position about 2500 yards south of the beach. Unleashed around the SANTA FE was the bombardment of amphibious warfare. Shortly before 0900 hours, a Niagara of taut-faced Marines in mottled garb cascaded over the transports' gray sides into waiting boats. Gaunt Suribachi glowered down on the hundred of American ships of every nomenclature which were milling around Iwo's approaches as the landing craft converged and swished shoreward through foamy surf. On Iwo Jima, wily General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, in command of the 22,000-strong Japanese garrison, solemnly hissed: "This island is the front line that defends our mainland and I am going to die here."

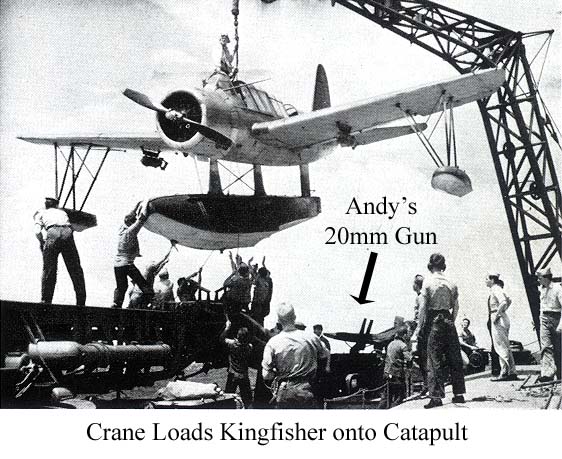

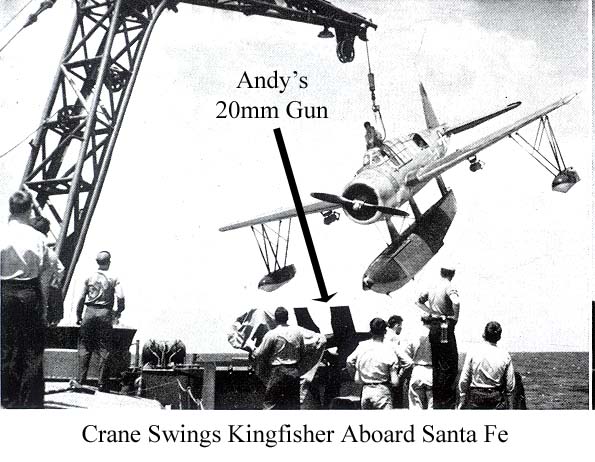

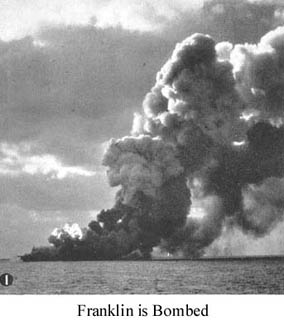

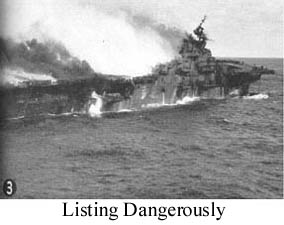

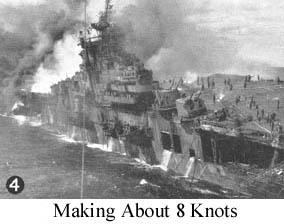

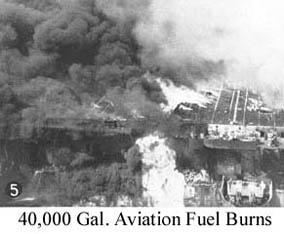

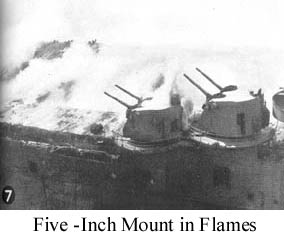

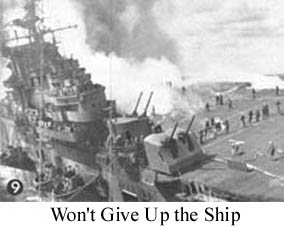

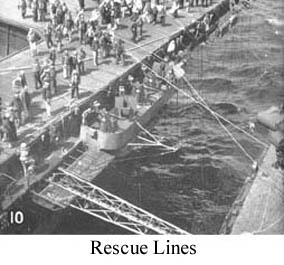

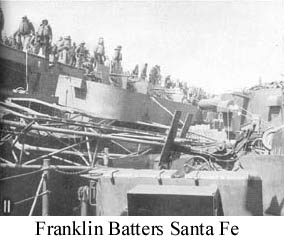

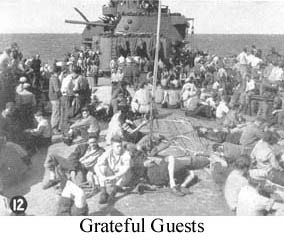

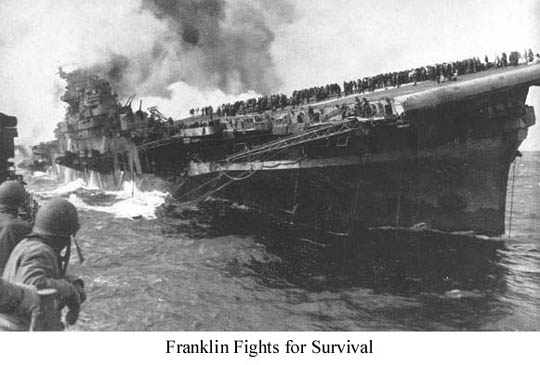

Aboard the SANTA FE anxious officers jammed her plotting room, juggling figures and pencilling charts. One Kingfisher was kept in the air for spotting purposes. About 1353 the light cruiser shifted her position, with her special target the western face of Mount Suribachi which rose starkly from the island's southern tip. Peeping out of pits and crevices on Suribachi were numerous railroad guns, AA guns, and observation posts. These were smashed and rooted out by accurate 6-inch shellfire from the SANTA FEís main battery. As the sun set over bleeding Iwo, the SANTA FE moved to the southeast and continued firing at assigned sectors throughout the night. Various missions were executed on 20 February by the SANTA FE, e.g. preparation fire for the morning assault, neutralization of mortar positions, a barrage against enemy artillery emplacements, and illumination fire ahead of the front lines to prevent a surprise night counter-attack. Japanese shellfire tore into the SANTA FEís observation plane, fatally wounding the Marine pilot. Strings of small caliber projectiles rained around the SANTA FE several times, but none of her sailors was hit. That evening the cruiser remained on the job off Iwo Jima, much of her fire being directed against enemy rocket launching areas. Relieved by the battleship NORTH CAROLINA at 1045 on 21 February, the SANTA FE ceased fire and steamed east to form up with the retirement group. That night she moved out to sea with the battleships, having contributed 989 rounds from her main battery, and 3027 from her secondary battery to the conquest of Iwo Jima. On the 22nd she returned to the transport area to replenish ammunition, but gave it up because of rough weather and headed east to rejoin her carriers. USS SANTA FE was in on a second Tokyo raid, carried out in bad weather on 25 February. Strikes were discontinued at 1212, after which the task force proceeded south with the intention of coming up and hitting Nagoya 26 February. An increase in the heavy weather precluded such an operation, and the SANTA FE's Task Group 58.4 moved to Ulithi on 1 March 1945. Rear Admiral Deyo shifted his flag to the BIRMINGHAM on. 9 March, and five days later the SANTA FE sortied from Ulithi as a member of Task Group 58.2. On the strike docket were further blows against the Empire. Snooper planes were observed during the approach on Kyushu, but no attack came from the skies. Reaching a position about 125 miles southeast of Kyushu on the morning of 18 March, the carriers commenced sending their squadrons aloft. Enemy planes in the vicinity made minor attacks on the other task groups, but none approached the SANTA FE closer than eight miles. Evening saw the carriers retiring to the southeast, but course was changed to north at midnight for an approach on Shikoku. First strikes were in the air about 0700 on 19 March 1945, the U.S. planes streaking off to hit Japanese fleet units in the Inland Sea. Suddenly at 0708, a Japanese dive-bomber darted down out the clouds. Pulling out of his dive at low altitude, he released two armor-piercing 500-pound bombs which plummeted into the big carrier FRANKLIN. One detonated beneath the carrier's flight deck on which her planes, weighted with bombs, rockets and machine gun ammunition, their belly tanks swollen with 100 octane gasoline were spotted ready for the take-off. Bomb No. 2 went off on the hanger deck where other planes were parked, fueled and armed, waiting to be taken to the flight deck. Carrier FRANKLIN became, in seconds, a floating ammunition dump in the process of blowing up. Men were blown off the flight deck into the sea, burned to a crisp in a searing white-hot flash of flame that swept the hanger deck, or trapped in compartments below and suffocated by smoke. Leathery black smoke funneled up to blanket the exploding flat-top, as nearby ships quickly jockeyed out of her way.

|