|

East

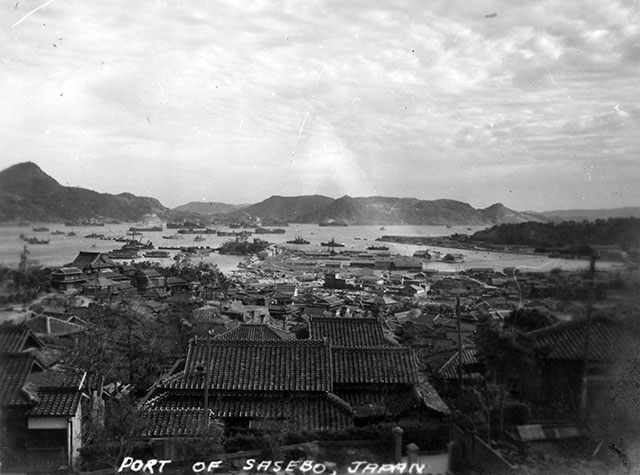

Meets West – By Philip D. Eakins Special to Sasebo Soundings Fifty-three years ago on Sept. 14, a small gray warship entered Sasebo harbor, signaling the beginning of the end of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s control of the Sasebo Naval Station. As the light minelayer USS Shannon (DM-25), flagship of Mine Division SEVEN, steamed past Kogosaki Point, the ship became “the first U.S. Man-o-War to enter these waters,” according to the Shannon’s September, 1945, War Diary. “I’ll never forget our entry into Sasebo. It was quite ominous,” remembered Grant Chipps, then an 18-year-old fireman first class aboard the Shannon. “I recall being told that we were the first foreign ship of any description to enter Sasebo harbor since the Japanese-Russian War ended.” The shore batteries located on both sides of the harbor entrance did not go unnoticed by the war weary crew. “we didn’t know what to expect,” said George Steimer, the Shannon’s Chief Signalman at the time. The crew had already witnessed the Japanese military’s determination to defend their territory at all costs, having participated in the bombardment of Iwo Jima and defending their ship against several kamikaze attacks during the nearly three months spent on radar picket duty off Okinawa. This time, however, the “Sassy Shannon,” as the ship was affectionately called by her crew, was given a special assignment: proceed to Sasebo to accept an informal surrender of the naval base. Twenty minutes after “dropping the hook” in Sasebo harbor, the Shannon received a delegation of Imperial Japanese naval officers led by Rear Admiral K. Ishii, Chief of Staff of the Sasebo Naval Station. Captain Henry Farrow, Commander, Mine Division SEVEN, accepted the informal surrender a short time later. Minesweeping operations were conducted with American and Japanese minecraft throughout the following week in preparation for the arrival of the occupation forces. Six days later the light Cruiser USS Santa Fe (CL-60), flagship of Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo, Commander, Task Force 55, steamed into port. During an occupation conference held aboard ship on the evening of September 21, Japanese Vice Admiral Sugiyama, commander of the Sasebo Naval Station, and Rear Admiral Hayashi formally surrendered the naval base to Rear Admiral Deyo.

The occupation of Sasebo began the following morning. According to the Santa Fe’s deck log, at 0700 “Task Group 54.2 commenced the occupation of the Sasebo area. The Fifth Marine Division commenced landing at various selected points throughout the harbor.” One of these selected points was the seaplane base at Sakibe. Francis L. Bitney was a 19-year-old Marine private first class and one of the first American troops to wade ashore that day to secure the facility. Assigned as a radio operator with Landing Force Air Support Control Unit #4, Bitney recalled being anxious as the landing craft lumbered toward the base. “Nearing shore we started getting a little concerned,” he said. “I didn’t think the Japanese army would be there, but I was wondering ‘what if there was even one person who’s seeking revenge?’” The Japanese navy, however, had deserted Sakibe, so Bitney and his unit spent their days cleaning up the area. “We never did any radio work,” he added. By the end of the day, Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill, Commander, Fifth Amphibious Force, reported to Rear Admiral Deyo that “approximately 10,000 troops landed in the area…no incidents noted, and the occupation is proceeding satisfactory (sic).” Soon the harbor was full of ships of all sizes and types, bringing thousands of sailors, Marines and soldiers to Sasebo. One of those sailors was Otis LeCornu, Jr., then a 20-year-old fire controlman petty officer third class aboard the light minelayer USS Thomas E. Fraser (DM-24). “We were really excited and at ease when we entered Sasebo. We hadn’t had our feet on the ground for a few months,” LeCornu remembered. During his first liberty ashore, LeCornu and a shipmate stopped in a bank near the train station to exchange some currency for souvenirs. Using a phrase book the Navy distributed to help sailors communicate with the Japanese, LeCornu said he tried his best to speak Japanese to the bank teller. “She looked up and asked me in perfect English what we wanted,” he recalled. “She said she had finished high school in Los Angeles; she was very sweet and helpful.” U.S. Navy ships weren’t the only vessels arriving in Sasebo. The liberty ship SS Allen C. Balch steamed into port loaded with supplies marked for Operation Olympic, the planned invasion of Kyushu that was scheduled for November of that year. Robert Hildebrand remembered being “very curious” about visiting Japan. The Maywood, California native was only 17 years old when the Allen C. Balch tied up at India Basin. “We did not know what to expect,” the former merchant marine said. “We had heard some pretty bad stories.” The ship carried many kinds of supplies, including beer, and it didn’t take long before everyone ashore and afloat had heard about this precious cargo. “At night or early evening you could walk across the harbor on all the liberty or shore boats lined up to get beer,” said Hildebrand. Liberty in Sasebo varied from ship to ship. For some sailors, time spent ashore was very restricted. “After a week we were allowed liberty, only in a group and with an officer,” recalled Leo Murphy, a former machinist mate petty officer first class stationed aboard the ocean tug (rescue) USS ATR 13. “No eating food, drinking, or fraternizing with the locals.” Murphy made only one trip into town before a typhoon hit Okinawa and his ship departed to assist in rescue and salvage efforts there. “Liberty, for the enlisted, was not exciting,” said Grant Chipps. “the officers had a place to go and get bombed. The officers club was one of the first American establishments in Sasebo, but for the rest of us liberty consisted of walking the streets and observing,” he added. Most of the local population had fled into the countryside or shut themselves up in their houses prior to the arrival of the occupation forces, leaving the city nearly deserted for those first few weeks. With much of the city in shambles as a result of an incendiary raid the previous June, many Americans considered Sasebo a depressing place to visit, especially upon seeing many homeless and destitute families with very little to eat. “If we had known what to expect we would have brought some food with us,” said George Steimer. In fact, many sailors and soldiers “liberated” canned food and candy from ship’s pantries or mess halls and gave them to families during return trips into town. Chieko Maeda remembered one time when her family took refuge behind some trees alongside the road at the sight of an approaching jeep. The jeep stopped near where she was hiding and the soldiers placed cans of food on the ground before driving away. “We were very lucky because we could eat that day,” she said. Shopping in Sasebo proved to be one of the biggest challenges faced by the occupation forces. With much of the downtown shopping area burned out, souvenir hunting became more like a treasure hunt. Shopkeepers were reluctant to accept occupation money, so many servicemen resorted to trading cigarettes for items such as dolls, fans, postcards or photos. The occupation of Japan officially ended in 1952. The relationship between the people of Sasebo and the base community remains as strong now as it did in those beginning days of mutual trust and friendship.

Additional photos received via email January 3, 2013

|